Jack London

White Fang

1906

That one was a beautiful book, lavished with imageries of nature to ravish our

heart and take it away. Strange to think this is all about a wolf, but while

other books take great pains to tell you of humans, London managed in a single,

supple, easy stroke to make us feel at all points and in all ways exactly as a

wolf would, in his mind, in his body, in his feelings. From the moment White

Fang is introduced, we go from observers of nature unravelling before us, eyes

strained at the immensity of it, to a conscious part of it. Nature is judged, characterised,

and, in true Naturalist fashion, given all the power. We’re a wolf and we never

go out of it, just like White Fang can only be what he is and what he is shaped

to be by his environment. I rarely met with a book that could get me as close

to an unnegotiated animal character and as far from the humans dealing with him

as this one (except for the Farseer and Tawny Man trilogies and I wonder

whether there isn’t some influence there. Would be interesting to look that up).

And as attached. It’s not an emotional attachment as much as survival instinct

instructing us poor human readers to cling to White Fang’s coat as fleece

might, never dare to let go. Of course, this is all about us. It’s always about

us. But while the metaphor was explicitly laid out, it never ceased being about

the wolf either.

And the novel is so well written, in a straightforward, Spartan sentence style, but with a digging of the one true word not unlike the style of haiku. London says it exactly as it is, yet he only speaks poetry. Albeit a sorrowful and heartbreaking poetry. It is a very wise book and one that aims to be so; not telling you a story as much as using the background of a story to explore living beings’ heart and soul. I was enthralled with the first page and if my enthusiasm sometimes wavered when the tale turned too cruel or too repetitive (London has the tendency to hammer the point in when he explains something. But his style is so clear, so knowing, that these further elaborations only encumber the book), it found me again only a few pages later. Clearly, Jack London knew how to write, so that I’m suspecting what he wrote about was not as important as his gift of writing to us. His style is like an adventurer: the persona takes over the nature of the adventure. And all that matters is that writing here is an adventure you just have to hop on.

And the novel is so well written, in a straightforward, Spartan sentence style, but with a digging of the one true word not unlike the style of haiku. London says it exactly as it is, yet he only speaks poetry. Albeit a sorrowful and heartbreaking poetry. It is a very wise book and one that aims to be so; not telling you a story as much as using the background of a story to explore living beings’ heart and soul. I was enthralled with the first page and if my enthusiasm sometimes wavered when the tale turned too cruel or too repetitive (London has the tendency to hammer the point in when he explains something. But his style is so clear, so knowing, that these further elaborations only encumber the book), it found me again only a few pages later. Clearly, Jack London knew how to write, so that I’m suspecting what he wrote about was not as important as his gift of writing to us. His style is like an adventurer: the persona takes over the nature of the adventure. And all that matters is that writing here is an adventure you just have to hop on.

P.S. As I understand it, London was a partially

racially-prejudiced man conscious of his prejudices and striving to rise above

it; hence, it’s difficult, when he qualifies the white men at the fort as

“superior” to the Native Canadians, to understand whether he truly sees them as

their superiors or is simply representing in White Fang’s terms the

relationship of hierarchy existing between the two at the time. His depictions

of the Native Canadians camp were also picked upon by people for its featured cruelty,

but the white men were portrayed just as badly so I did not find any offense in

it. It was rather as humans that readers could take offense.

Kenneth Grahame

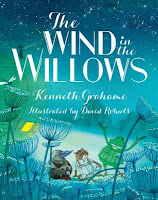

Kenneth GrahameThe Wind in the Willows

1908

The most poetic book of prose I’ve ever encountered, The Wind in the Willows is designed to make you happy, which, to me, as far as novels go, generally works to make them better. Accept precariousness and enjoy the day, it says, but without failing your needs and responsibilities, without falling prey to a preaching of letting go of all. It’s about the peace one can find in living life rather than living one’s life, though the book champions firmly and fiercely the right to individuality.

Four very different animals will be our companions, and page after page you realise how human_ yet not just so_ they actually are. Mole is the animal most “like” everybody, which is why we start off with him. Ratty is my personal favourite, so poetic and generous, so earnest and easy. Toad is readers’ most popular character, I think, and he would like that. Old Badger and his charming cozy house is clearly the inspiration behind the Hobbits of Hobbiton, Bywater, and Bag End. Everything about Badger and his home sounds like an older animal version of the advice given by the ale-drinker in The Green Dragon, with the certainty of the ignorant: “Keep your nose out of trouble, and no trouble'll come to you."

Trouble always comes. The book suffuses peace, yes, but does not deny troubles. Without giving you one easy solution to the acknowledged downsides of life, The Wind gives you hope. It infuses you with courage. And when one trouble is solved, the book shrugs its shoulders and seems to wave to Trouble a knowing “Till we meet again…”

If The Wind invites you to snuggle up within its warmth, it never preaches settling; for it’s about change, and, as inevitable as the mouvement of the seasons, change comes through the adventures of the four friends whose themes will range from well-being, the unknown, addiction, life in society, power, wealth, status, propriety, shame, horror, fears, administrative leeching, to the Divine…

Finally, it’s about caring about and for others; about the sheer beauty of nature; the sweetness of life, of the “wild”; all of which you are narrated with just the right touch of humour, wisdom and restraint. In his rich writing, Grahame finds a thousand ways of saying the simplest things, particularly when addressing the river in an invite of words to lushly and leisurely slide on it with him. You do not read The Wind in the Willows; you live it, going from one ambiance to the next in this quite fairy-like, otherworldly, animal life. The telling of the tale is what you might feel if only you opened your eyes to the world around, so very near, opened your eyes to what you see every day but never really look at… What if home was this less-than-perfect thing claiming our return after a long and necessary voyage? What if home was actually nature and people? What if home was to be found at last in what we had antagonised?

A very inspirational piece, it’s actually the most therapeutic work I’ve ever read. With this deeply intelligent tale, Kenneth Grahame gives you the most adult of all children’s books. It feels as home should.

Tags: a toad, a badger, a water rat and a mole, Toad's role-playing, more of Toad's role-playing, the river bank, late 19th-early 20th-century mood, pastoral England, accepting that everybody has flaws, that everybody brings in something new, on hooves and mysticism, moody winter nature, British wit, nostalgia for the adventure of life, nostalgia for the peace of home, adventures and misadventures or how to look for the perfect thing, life without governance, nature's society vs. urban society, life, death and everything else found on a river bank, Toad of Toad Hall or a portrayal of bourgeoisie

No comments:

Post a Comment